What’s a defect? I like this definition.

A defect is anything that threatens the value of the product.”

Before we start, let’s agree that:

- we don’t want to have defects that threaten the value of our product

- we want to give our customers as much value as possible at all times.

If you don’t agree with 1 and 2 then, don’t waste your time and stop reading now.

Testers are normally associated with finding defects. Some testers get very protective with the defects they find and some developers can be very defensive about the defects they wrote. Customers don’t like defects, developers don’t like defects, product managers don’t like defects, let’s be honest, nobody likes defects besides some testers.

Why would that be? The reason is that the focus of testers is on detecting defects, and that’s what they get paid for in most organisations. If you are a tester and love your defects, you might find this article quite distressing, if you decide to proceed, do so at your own peril.

Let’s be clear from the start: defects are waste. Waste of time in designing defective products, waste of time in coding defective routines, waste of time of detecting them, waste of time in fixing them, waste of time in re-checking them. Even writing this sentence took a good while, now think how much time it takes you to produce, detect, fix, recheck defects.

Our industry has developed a defect coping mechanism that we call defect management. It is based on a workflow of detecting => fixing => retesting. Throughout the years it has become best practice (sic) to have defect management tools and to log and track defects. Defect management approaches are generally cumbersome, slow, costly and tend to piss people off no matter whether you are a tester that gets his defect rejected, you are a developer that gets a by design feature flagged as defect or you are a product manager that needs to spend time prioritising, charting and trending waste.

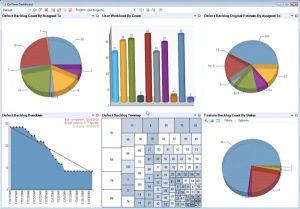

Another bad characteristic of defects is that they can be easily counted and you will always find a pointy haired manager that decides he is going to shed light on the health of his product and on the efficiency of his test team by counting and drawing colourful waste charts.

But, before we said that defects are waste, why are we logging and tracking waste, creating waste charts seems even more ridiculous, wouldn’t it be easier to try to prevent them?

Oh, if only we could write the right thing first and reduce the amount of defects! I say we can, be patient and read on.

Software development teams have found many ways of being creative playing with defects, see some examples below.

Example 1: Reward waste

Some years back i was working on a business critical project in one of 5 scrum teams . Let me clarify first, that our scrum implementation was at best poor, we didn’t release every sprint and our definition of done was questionable.

Close to an important release we found ourselves in a situation where we needed to fix a lot of defects before going into production. We had 2 weeks and our teams had collectively around 100 defects to go through. Our CTO was very supportive of the defect killing initiative and he was eager to deliver with zero defects. He put in place a plan that included free food all day and night and some pampering for the developers that needed to focus 100% on defect resolution. Then he decided to give a prize to the team that would fix the highest amount of defects.

I remember feeling frightened of the possible future consequences of this reward. I spoke to the CTO and told him that I would have liked more a prize for the team that produced the lowest amount of defects rather than the one that fixed the most. Our CTO was a smart guy and understood the value proposition of my objection, he changed his approach and spoke to the teams on how not introducing defects in the first place is much more efficient than fixing them after they have been coded. Soon after the release we started applying an approach that focussed on preventing defects rather than fixating on detection. We never had the problem of fixing 100 bugs in 2 weeks again.

Example 2: Defects metrics

In my previous waterfall life, I remember when management introduced a performance metric directly linked to bugs. Testers were to be judged on the Defect Detection Index calculated as (Number of Defects detected during testing / Total number of Defects detected including production)*100. An index lower than 90 would mean nobody in the test team would get a bonus. Developers were individually judged on number of code defects found by the testers and business analysts were individually judged on number of requirement defects found by the testers.

The bug prioritisation meetings were battles where development managers argued any bug was a missed requirement, product managers argued that every bug was a coding error or a tester misunderstanding and the test lead (me) was simply shouted at and criticised for allowing his testers to go beyond the requirements and make use of their intellectual functions outside a scripted validation routine.

Going to that meeting was a nightmare, people completely forgot about customers and simply wanted to get their metrics right. The amount of time we wasted arguing and defending our bonuses was astonishing. Our customers were normally unhappy because instead of focusing on value delivery we focussed on playing with defects, what a bunch of losers we were!

Example 3: Defects as non conformance to requirements

In the same environment as Example 2 testers, in order to keep their Defect Detection Index high used to raise large amounts of minor or non significant “defects” that were in reality non conformance to requirements that generally represented improvements. Testers didn’t care if they were requirements, code defects or even improvements, to them they were money, so they raised them. Improvements were filed as defects as they were in non conformance to requirements. In most of the cases these were considered low severity and hence low priority defects to make the testers happy and had to be filed, reviewed, prioritised and used in trends, metrics and other useless calculations. This activity could easily take 30% of the tester time. Such defects would not only take testers’s time, but would affect developers, product managers, business analysts and eventually clutter the defect management tool. Waste that creates waste, exponentially, how wonderful.

Example 4: Defect charts, trends and other utter nonsense

Every week I had to prepare defect charts for management. These were extracted from our monstrous defect management tool and presented in brightly coloured useless charts. My manager got so excited at the prospect of producing useless information that she started a pet project to create charts that were more colourful than the ones I presented. She used 2 developers for 6 weeks to create this thing that was meant to wow the senior executives. In the process of defining the requirements for wowing the big guys she introduced a few new even more useless charts and consolidated it into an aggregating dashboard. She called it the product quality health dashboard, I secretly called it the dump. Nobody gave a damn about the dashboard, nobody used the numbers for any reason, nobody cared that they could configure it, but my boss was extremely proud of it. A legend says that she got a big raise because of it. If you play with rubbish, then you will start measuring rubbish and eventually you will end up doing data analysis and showing a consolidated view of the rubbish you store in your code.

How can we avoid this?

1. Focus on defect prevention

Many development teams focus on delivering features fast with little consideration for defect prevention. The theory is that testers (whose time is sometimes less expensive than developers) will find the defects that will be fixed later. This approach represents a false economy; rework disrupts developers activities and harms the flow of value being delivered. There are many approaches available to development teams to reduce the amount of rework needed.

Do you want to prevent defects? You can try any combination of the below:

- With BDD/ATDD/Specification By example, delivery teams test product owners assumptions through conversations and produce the right feature the first time.

- The ability to have fast feedback loops also allows for early removal of defects, automated unit and integration testing can help developers quickly identify potential issues and remove them before they get embedded into a feature.

- Tight collaboration between business and delivery teams helps teams be aligned with their real business goal and reduce the amount of unnecessary features. This means less code and as a consequence less defects. Because, your best piece of code is the one you won’t have to write.

- Reducing complexity is very powerful in preventing defects, if we are able to break down a complex problem in many simple problems we are likely to reduce the amount of defects we introduce. Simple problems have simple solutions and simple solutions have less defects than complex ones.

- Good coding standards like for example limiting the length of a method to a low number of lines, setting limits on cyclomatic complexity, applying good naming conventions to help readability also have a positive impact on the number of defects produced

- Code reviews and pair programming greatly help reduce defects

- Refactoring at all times also reduces defects in the long run

Moral of the story: If you don’t write defects, you will not have to fix them.

2. Fix defects immediately and burn defect management tools

If like me years back, you are getting tired of filing, categorising, discussing, reporting, ordering defects I have a very quick solution. Fix the defects as soon as you find them.

It is normal for a developer to fix a defect he finds in the code he is writing as soon as he finds it without having to log it, but as soon as the defect is found by a different individual (a tester for example) then apparently we need to start a strict logging process. Why? No idea really. People sometimes say: “if you don’t do root cause analysis you don’t know what you are doing, hence you need to file the defects”, but in reality nobody stops you from doing root cause analysis when you find the defect if you really want. What I am suggesting is that whoever finds a bug walks to a developer responsible for the code and has a conversation. The consequence of that conversation (that in some cases can involve also a product owner) should be let’s fix it now or let’s forget about it forever. Fixing it now, means normally that the developer is fresh on the specific code that needs to be fixed, certainly fresher than in 4 weeks when he won’t even remember he ever wrote that code. Fixing it now means that the issue is gone and we don’t have to worry about it any longer, our customer will be thankful. Forgetting about it forever means that it is not an issue worth fixing, probably it doesn’t threaten the value of the project and the customer won’t care if we don’t fix it. Forgetting about it forever also means that we won’t carry a stinky dead fish in a defect management tool. We won’t have to waste time re-discussing the same dead fish forever in the future and our customers are happy we are not wasting time but working on new features. If you decide to fix it, I’d also recommend you write an automatic test around it, this will make sure that if the issue happens again you’ll know straight away.

I have encountered huge scepticism when suggesting to burn defect management tools and fix just in time. Nobody seems to think this is possible. As a matter of fact my teams were able to do this for the last 5 years and nobody ever said, “I miss Jira and the beautiful bugs”.

Obviously this approach is better suited for co located development teams, I haven’t tried it yet with a geographically distributed team, I suggest you give it a try and let me know how it goes.

Playing with defects waste index:

Epidemic: 90% – The only places that don’t file and manage defects I have ever encountered are the places where I have worked and have changed the process. I have heard of one other place where they do something similar but that’s just about it. The world seems to have a great time in wasting money filing, categorising, reporting, trending waste. The IT industry has been doing this for decades and questioning the approach is generally seen as heresy.

Damaging: 100% – Using defects for people appraisal is one of the worst practices I have ever experienced, the damage can be immense. The customer becomes irrelevant and people focus on gaming the system to their benefit. Logging and managing defects is extremely wasteful as well, it requires time, energy and can among other things, endanger relationships between testers and developers. Trending and deducting release dates from defect density is plain idiotic, when with a little attention to defect prevention defects would be so rare that trends would not exist.

Resistant: 90% – I had to leave one company because I dared doubt the defect management gospel and like an heretic I was virtually burned at the stake. In the second company I tried to remove defect management tools I was successful after 2 years of trying, quite resistant. The third one is the one where people were happy to experiment and as soon as they saw how much waste we were removing it quickly became the new rule. I have had numerous discussions with people on the subject and the general position is that defect management must be done through a tool and following a rigid process. I believe it is a very difficult wasteful practice to eradicate.

Recommended Reading

Lean Software development – An Agile Toolkit (Mary and Tom Poppendieck)

https://mysoftwarequality.wordpress.com/2015/05/06/little-tim-and-the-messy-house/

Hey Gus,

Nice post, thanks for taking the time to put it together & sharing.

I do agree with your points in the large – managing bugs is waste, but sometimes we have to put up with that waste for a period of time (perhaps because there’s a bigger pile of waste we need to get rid of first :-))

There are a few leaps & assumptions in your post that appear to have worked in your situation but I can imagine some scenarios where your ideas may fall down, such as:

“The consequence of that conversation (that in some cases can involve also a product owner) should be let’s fix it now or let’s forget about it forever.”

There may be occasions that do require a bug to be deferred, such as more important/pressing deadlines or lack of people to fix the bug right now.

Interestingly, I am with a client at the moment who uses offshore development teams. The guidance from my client to the offshore org is that (paraphrased) they are not interested in bugs being raised during the development cycle.

For the first time in a long time, I am finding the bugs that have been logged very useful – they do provide an RCA for each bug & it’s those stats that provide the evidence for my recommendations. There are obviously a load of assumptions based on those stats (such as the RCA is correct) as I don’t have time to check each bug.

Bugs in my context are being used to track the quality of software when it is delivered back to my client. This is a smell in itself, but it is serving a purpose for now until the bigger problem(s) can be addressed.

Thanks again for the thought provoking post Gus, will be good to catch up again soon,

Duncs

P.S. 2 of my go to posts regarding bugs:

https://agiledreamer.wordpress.com/2012/03/14/bugs-are-not-bugs/

LikeLike

Hi Duncan,

Thanks for your feedback and examples you provide.

The main article is by no means trying to say that defect management is always the wrong answer in every context. I appreciate the existence of situations like the ones that you describe, where some level of logging can be useful.

On the other hand, I have witnessed situations where a leaner approach would have been easy to implement, but the “best practice” of logging bugs was overriding any reasonable observation. This article, and the other ones in this blog, invites readers to reflect and see if a leaner approach could apply to their context.

LikeLike

Entertaining and spot on!

I wish I can say this is the first time I hear about this. Unfortunately I have been in the same or similar situation as your examples numerous times. And I guess still am 😉

I remember working with a talented QA in a small company (team size of 4). She would log a bug for the simplest of things, even if I am sitting next to her. So I will know about the bug from my email… Many times I will understand, produce, test and commit a fix for the time she used to write a long and detailed description of the issue. Eventually she started to share more and we started to fix it all immediately.

Why did she even did it in the first place? In her previous job she was rewarded for bugs reported (Reward defects, Defect metrics). She also said she likes to log the bugs so we keep track on them and revisit them in the future. Did we ever revisited them? Not even once for three years. It is just how she was used to work. Epidemic indeed!

Thank you for sharing!

LikeLike

Thanks for your feedback and example Kostadin, they are very much appreciated.

Think now, can you help your organisation make a small change, remove a lot of waste, and eventually save money? If you can, go for it, the person that fits the bill will be grateful forever!

LikeLike

I liked this post very informative. I have been in testing along time waterfall and various flavors of Agile. While I agree with some of this, I thing logging defects is a must as, we need to have accountability for what we do and also covering your own arse. I currently work for a company where our UAT team or owner of the company seems to think that blame comes down to me not testing properly, the fact I may have found in the region of 150 defects/improvements seems to slip his mind when all in he could was 5 minor issues.

what he did find was so low value that is was a waste of effort to write them up.

We do discuss some issue we find as that can be productive and as this company are very new to agile , shaping to use this kind of process might work,but for me I like to have a mechanism to report issue.

LikeLike

Nico, thanks for your feedback. If you have trust issues that cause blame, you then need to resolve them first and then get back to doing software development. Trust is fundamental and it’s not by adding contracts (bug reports) that you improve it. Somebody said “Customer collaboration over contract negotiation”

LikeLike

You might like that definition of defect, but James never said that (nor have I). It’s weird that you you’d cite a reference to his work in which he explicitly says that he does not say what you say. “Defect” is a deprecated word in the Rapid Software Testing namespace, for at least three reasons:

>We as testers (and even, arguably, we as developers) don’t know that something is a defect until someone with authority declares it to be a defect.

The word “defect” unnecessarily creates an extra level of antagonism in our relationships with people. (We prefer “bugs”. Observe the reaction that you get when you say “your behaviour is defective”, and compare that with “something about your behaviour bugs me”.)

The word “defect” has a specific meaning in legal contexts.

Your assertion that “nobody likes defects except some testers” is weird to me. I think you might mean “nobody like harping on defects”, or “nobody wants to talk about defects”. For that, I’d refer you to the first paragraph of this interview with Jerry Weinberg. It’s important that we talk about problems because solving problems is of the essence in development work. Learning how to solve problems involves discovering those problems, and studying them, and learning about them.

You say that “defects are waste”. But you haven’t really described what defects are (other than by misquoting James), nor have have you described waste. It’s easy to say “prevent all defects!”, but we could easily do that by saying “prevent all mistakes”, “prevent all experiments”, or “prevent all action”. Apparently you’re not saying that. So what are you saying?

LikeLike

Michael, have you ever thought that the word defect or bug might be used by people differently from you and James? Are these people all wrong? Do you own a trademark on the words defect or bug? Am I infringing any law by using a different definition?

But mainly, do the rest of the word care what you deprecated and what not?

I am removing the reference to James as it seems to have caused controversy. If you have some other comment beyond semantics, I’d like to hear from you.

LikeLike

Gus…

Let’s remember how your blog post originally began:

“What’s a defect? I like this definition.

A defect is anything that threatens the value of the product. —James Bach”

Of course I believe that other people might use the word “defect” differently from me or James. And there’s nothing wrong with them doing so, either. That’s okay.

I doubt very much that the rest of the world, other than a vanishingly small part of it, cares what we have deprecated or not. But WE care. We care about our reputations, and we care about taking responsibility for the words that we use. What is NOT okay, in my view, is to put words in other people’s mouths as you did in the first version of this blog post. That is misrepresentation. We spend a lot of time and effort being careful about what we say. Taking responsibility for your words may not matter to you, but it matters to us. It matters a lot, because our words are tied up with our reputations and our credibility.

People are not wrong to use words in the ways that they choose, although when the words are subject to interpretation and misinterpretation, it might be quite helpful if they could be explicit about what they were talking about.

Semantics is the branch of knowledge and understanding concerned with the relationship between words and meaning. If you declare that semantics aren’t important, you’re declaring that words and meaning aren’t important. It doesn’t take very long to go from that to saying that there’s no relationship between what you say and what you mean, or that if I say something you don’t care what it means either to you or to me.

Now, if you don’t care about the link between words and meaning, it becomes possible for you (1) to claim that James said that a defect is anything that threatens the value of the product (which he didn’t); or (2) that or that the sun is a grape (which it isn’t); or that experiments that don’t work out as we had hoped—but from which we learn something—are intrinsically and exclusively waste (which they are not).

The trouble with all that is not that you are infringing on any law, but that (in the first case) you make assertions that are simply untrue and that misrepresent what other people say—and thank you for acknowledging this and fixing it; (in the second case) you would be saying something that will make people believe that you are stupid or crazy (which not even I believe); or (in the third case) that you will oversimplify things to the degree that you will say something fatuous and shallow like “fix all defects as soon as you find them”.

Fixing a defect as soon as you find it is easy when the product is in development, when observing the defect is straightforward and when its cause is obvious; when it’s a simple coding error that makes sense to fix today. But sometimes a problem is subtle, and the fix comes with mixed consequences. For instance, a company that I’ve been working with received a report from the field about something that everyone would agree was a design problem (would you call this a defect?) in a piece of firmware. That firmware had interdependencies with four pieces of software and three pieces of hardware. Fixing that design problem and deploying it would beautifully resolve a problem in one of the software products in the field; have no effect on a second; would change a workaround into a crash on the third; and would, out of the blue, break the fourth until all four software products could be upgraded. Systems that contain one piece of hardware would be amenable to the redesign, and largely be unaffected by it; systems that contain a second would actually benefit from it; and systems that contain a third would be made instantly incompatible by it—not a problem two years from now, when updates have been rolled out across the customer base, but a real problem for its users today.

Do you see? Some problems simply aren’t simple. Some are more challenging. In order to deal with complex, challenging problems, we need—in my view, at least—more engineering and less sloganeering. When someone asks a difficult question, we need—in my view, at least—to rise to the challenge and answer it. Or at least, I’d say we need to do so if we want to be understood. In your case, your call, of course. But have you noticed that you didn’t answer my question? You haven’t said what you meant by “waste,” so I’ll ask again: what are you saying?

LikeLike

Hi Michael, thanks for your feedback.

Firstly, if I take your feedback onboard, and CHANGE my content in line with your feedback I expect a thank you and not a lecture on how the blog read when it was wrong, but obviously, I am an optimist.

Secondly. Since the name of your colleague has been removed from my article, there is nothing that links my content to any of you, you can breath, your reputation is intact. At this point, I feel I can use the words bug or defect the way I like.

All your lecture on semantics can be forgotten because it was a lecture that you insisted in giving me even after I removed any trace of the name that had created the earthquake.

Thirdly, on the fact that I might say something fatuous and shallow, I am completely aware of that, I am human and don’t have a problem making mistakes, I learn every time I make one.

Fourthly, you gave me ONE example of ONE unusual bug that couldn’t be fixed immediately, great, that sounds like the exception that proves the rule. Should we build all that waste because we might be affected by that one strange case or could we fix everything immediately and have an exception for a rare category of defects?

LikeLike

(Earlier) I am removing the reference to James as it seems to have caused controversy. If you have some other comment beyond semantics, I’d like to hear from you.

(Later) Firstly, if I take your feedback onboard, and CHANGE my content in line with your feedback I expect a thank you and not a lecture on how the blog read when it was wrong, but obviously, I am an optimist.

I did give you a thank you. And you asked me for some other comment, which I gave you. Since I gave you what you asked for, I’d expect a thank you, but obviously I’m an optimist.

Should we build all that waste because we might be affected by that one strange case or could we fix everything immediately and have an exception for a rare category of defects?

I’d be pleased to answer that question if you can tell me what you mean by “defect” (as I asked in my first reply) and “waste” (as I asked in my first and second replies). To that list, I can now add “everything” and “immediately”. It would also be cool if you could provide me with a formula for determining what is wasteful a priori.

Since you don’t like my “one strange case” (which I can assure you, based on 25 years or so in software development, is not at all strange), I’ll give you an example from the other end of the spectrum. A programmer comes to work in the morning. He’s been given a problem to solve. He ponders a problem for a little while, and codes a solution to it. He creates an object, writes a few useful member functions, does a little testing, and performs a few more experiments. After a few refinements, he’s satisfied. After lunch on that same day, while having coffee, he realizes that he was all wrong all along. There’s a better way; break the object up into two different objects that encapsulate the data and the functions a lot more cleanly. Ta-da! Much better.

My questions are: 1) Was the first approach defective? If you asked the programmer, would he say so? If you asked another programmer, would she say so? And would the answer depend on when you asked?

2) If the answer to the first question is yes, was the first approach wasteful?

3) Given that the programmer might have pondered the problem for several days before arriving at the second solution, can we say that the morning’s effort was wasteful?

Oh, if only we could write the right thing first and reduce the amount of defects!

That’s exactly the philosophy behind the waterfall: get it right the first time. I don’t think you mean to promote that. So what DO you mean?

Code reviews and pair programming greatly help reduce defects

If I’m sitting with a programmer, and point out something during a code review that the programmer decides to fix, has a defect happened or not happened? Isn’t a code review something that focuses on detecting defects? If not, what is it?

Refactoring at all times also reduces defects in the long run

Is code that needs refactoring defective or not?

These kinds of questions may be irritating to you. They may sound like nitpicking. But remember that one of the very patterns that you deplore (detecting => fixing => retesting) is exactly the pattern that expert programmers engage in when they’re performing TDD. I don’t think you mean to deplore that. So what DO you mean?

I can’t tell for sure, of course. But I can offer a few things:

0) I’d say that something is wasteful when, based on experience, we can declare that it caused extra and unnecessary effort, that it caused more problems than it solved, or that it destroyed more value than it created, and that we didn’t learn a damned thing from it. We can anticipate wastefulness based on experience, but it’s important to remember that perception of waste is relative to the observer. Something that seems like a waste of time to you (this reply, for example) may be immensely valuable to me if I learned something from it (which I’ve done).

1) I agree that many of the trappings around “defects” (the counts, the graphs, the bogus reward systems, the goal displacement) are unhelpful and wasteful. Much of this is based on the the fact that…

2) The concept of “defects” is muddy and unhelpful (mostly for reasons I outlined in my first comment). Instead, let’s think in terms of problems—situations that are undesirable to some person, and probably solvable by some person, although probably not without some effort. Given that,…

3) I’m not opposed to detecting problems; I’m very much in favour of detecting them. I’m in favour of doing it at every opportunity, ideally at the earliest opportunity. I want to be an expert at detecting problems because…

4) If we’re not very, very good at detecting problems, we’re not going to be very good at preventing them. That’s because it takes a significant amount of preparation, anticipation, and critical thinking to recognize a problem (or a potential problem) early enough to “prevent” it—which I think really means detecting it or its causes early enough to prevent it from becoming a bigger, or deep, or rare, or hidden, or subtle problem. That’s a skill set I’d like everyone on the team to have. For extra critical distance, get a tester.

5) I’m opposed to empty slogans “defects are waste” when they oversimplify complex systems of behaviour, learning, and development. It doesn’t take too long to go from “defects are waste” to “don’t make mistakes”—and one great way not to make mistakes is not to try anything.

6) Another reason I’m opposed to slogans like “defects are waste” is the schoolmarmish tone based on the presumption that we can know in advance what is wasteful and what is not. That smacks way, way too much of the waterfall and the factory for my taste, and it’s weird to hear it coming from so many Agilists.

—Michael B.

LikeLike

MB I’d be pleased to answer that question if you can tell me what you mean by “defect” (as I asked in my first reply) and “waste” (as I asked in my first and second replies).

As stated in the post “A defect is anything that threatens the value of the product.”

For waste you can refer to Taiichi Ohno’s definition https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Muda_(Japanese_term)

MB ( To that list, I can now add “everything” and “immediately”. It would also be cool if you could provide me with a formula for determining what is wasteful a priori.>

I would point you to your favourite English language dictionary, I believe that re-defining well known terms is a wasteful activity and I try not to engage in such activities. As you have probably already read the link I shared above you will know that engaging in such conversation is the type of waste called Overprocessing.

As per the formula, I don’t have it, it is based on the latest release of “Common Sense 1.x” available in most human beings.

MB Example of developer changing his mind

Based on the definition of defect on this very post, the programmer is re-factoring a previously working solution, hence he is not fixing a defect as such but he is improving the efficiency and maintainability of the code without changing the business value. This if I understood your example.

MB < Was the first approach defective? If you asked the programmer, would he say so? If you asked another programmer, would she say so? And would the answer depend on when you asked?>

I don’t think it was, but to be honest as long as he re-factors the code I am happy and won’t be annoying him or any of his colleagues with semantic questions once the delivery of value is complete. Other activities that don’t produce value are Overprocessing.

MB 2) If the answer to the first question is yes, was the first approach wasteful?

The answer to the first question is I “I don’t think but mainly I don’t care” so this question gets skipped

MB 3) Given that the programmer might have pondered the problem for several days before arriving at the second solution, can we say that the morning’s effort was wasteful?

No, he performed 2 activities, coding and re-factoring. As he, like every other human, is not perfect he’s allowed to change his mind. Maybe he needed to see the code in the previous format before he realised it could be done differently. He will learn from this activity and the next time he needs to deliver something similar he will go straight for the good solution.

It could have been more efficient to have him pair with a more experienced programmer at design time. This is what would happen generally in my teams, and even if no pairing happened, sometimes at code review, more than likely somebody more experienced would have suggested the new solution.

MB That’s exactly the philosophy behind the waterfall: get it right the first time. I don’t think you mean to promote that. So what DO you mean?

Have a look at how BDD works for example, you will find the answer there.

MB If I’m sitting with a programmer, and point out something during a code review that the programmer decides to fix, has a defect happened or not happened? Isn’t a code review something that focuses on detecting defects? If not, what is it?

You prevent it from going into trunk. Whether a) it existed, b) didn’t exist, c) it was a Schrodinger defect that existed and didn’t exist at the same time is NOT important and discussing it over and over is guess what> Overprocessing. If we go to the pub and we have a couple of pints then we can discuss it as long as we want. The really important thing for my CUSTOMER is that code reviews on a pull request prevent defects from going into trunk and reduce the waste in detect fix retest.

MB: Is code that needs refactoring defective or not?

Based on my definition above NO. The value is delivered to the customer whether the code is re-factored or not.

MB These kinds of questions may be irritating to you. They may sound like nitpicking. But remember that one of the very patterns that you deplore (detecting => fixing => retesting) is exactly the pattern that expert programmers engage in when they’re performing TDD. I don’t think you mean to deplore that. So what DO you mean?

These questions sound like nit picking to me yes. Discussing them for more than 5 minutes is definitely wasteful, in particular because I answered these questions the first time that the scenarios you came up with happened to me, I applied a solution and don’t need to go over it every time that it happens to me.

TDD goes Red => Green => Refactor really nothing to do with detecting => fixing => retesting. Can you give me a source that is not your reply where somebody says that TDD is detecting => fixing => retesting?

I have done TDD for 10 years and it never occurred to me, I look forward to learning something new.

MB I’d say that something is wasteful when, based on experience, we can declare that it caused extra and unnecessary effort, that it caused more problems than it solved, or that it destroyed more value than it created, and that we didn’t learn a damned thing from it….

Now I understand the misunderstanding, I use Taichi Ono’s definition of waste, not yours, I thought it was obvious but I was wrong. Again, have a look at his categories of Waste, I’m sure it will clarify it. I will add a note on my blog where I refer to Ono’s 7 categories of waste to avoid misunderstandings.

MB If we’re not very, very good at detecting problems, we’re not going to be very good at preventing them

I agree. In fact we use testers to help us prevent defects, that’s what I discuss here (https://mysoftwarequality.wordpress.com/2014/10/12/the-agile-tester-a-curious-and-empathic-animal/) and in part 2.

MB I’m opposed to empty slogans “defects are waste” when they oversimplify complex systems of behaviour, learning, and development. It doesn’t take too long to go from “defects are waste” to “don’t make mistakes”—and one great way not to make mistakes is not to try anything.

Have a look at Taichi Ono’s literature on waste on this subject (same as the above) and see if it clarifies the context. It is certainly not an empty slogan, there is plenty of literature about it.

MB Another reason I’m opposed to slogans like “defects are waste” is the schoolmarmish tone based on the presumption that we can know in advance what is wasteful and what is not. That smacks way, way too much of the waterfall and the factory for my taste, and it’s weird to hear it coming from so many Agilists.

I admit, I had to google schoolmarmish. Coming from you brings to mind “Pot, meet kettle” but besides that, the misunderstanding is still based on the fact that it was not clear what waste definition I was using,

It’s a pity Taichi is dead, he would have loved being called schoolmarmish because he said “defects are waste”.

To finish, you talk about waterfall referring to my work, the only thing I can say is, it is a real pity you weren’t listening when I showed you our process and approach here in Dublin.

LikeLike

[…] This is a reviewed and improved version of an article I first wrote in 2015 (old version here) […]

LikeLike